The issue of “debanking” has taken center stage in the UK as British Muslims share stories of sudden account closures and financial exclusion, leading to broader calls for transparency and fairness in the banking industry.

In a recent case, Iqeel Ahmed, a former postman from Luton, found himself locked out of his Halifax bank account, rendering him unable to provide for his family. After six weeks of unanswered questions, Ahmed’s account was reinstated following the submission of identification.

However, to his bewilderment, he and his wife later received letters from the bank stating that their relationship was no longer tenable. Even their children’s savings accounts were closed, leaving Ahmed both puzzled and concerned about the lack of explanation.

Similar experiences have been shared by many in the British Muslim community. The issue gained prominence when prominent Brexit campaigner Nigel Farage revealed his account closure by NatWest’s Coutts subsidiary, leading to a wider conversation about debanking practices.

For Muslim individuals, the challenge of accessing financial services has been exacerbated by difficulties in applications and clearance checks, as well as unexplained account closures.

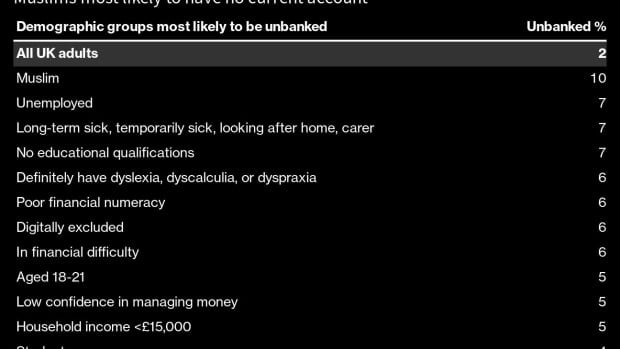

The Financial Conduct Authority’s data from the past year revealed that about 1 in 50 UK adults are “unbanked,” a figure that rises to 1 in 10 for Muslims. In response to mounting concerns, the Muslim Council of Britain has called for an impartial review to ascertain if there is a disproportionate trend in account closures among the Muslim community.

Debanking is driven by a global crackdown on money laundering and corruption, but the consequences for individuals can be severe. Banks have escalated their account closures in the UK, with nearly 350,000 shut down last year compared to 45,000 in 2017. Despite this surge, over 1,300 individuals complained about account closures to the financial ombudsman, many without receiving an explanation.

Wasif Mahmood, a financial services lawyer, has taken on several debanking cases affecting marginalized communities, including small business owners and overseas students. Mahmood points out that debanking has cascading effects, creating a cycle of missed opportunities.

Among his clients are individuals from immigrant, Muslim backgrounds who operate cash-and-carry shops, often targeted due to perceived money laundering vulnerabilities.

The issue of financial access for Muslims is not new. In 2014, HSBC faced criticism for closing accounts of Syrian refugees and mosques. Wrongful links to terror activities prompted apologies and compensation. Cases like these highlight the need for more nuanced risk assessments.

The ongoing challenges faced by individuals in the Muslim community also extend to the early stages of their banking journey. Many are rejected at account opening due to reasons like non-acceptance of travel documents or potential sanctions matches based on their names.

As discussions surrounding debanking practices and financial inclusivity gain momentum, there is a growing demand for increased transparency in the risk assessment and decision-making procedures of banks.

The banking industry is under pressure to address potential biases within its systems and ensure more equitable access to financial services for all customers, regardless of their background.

WhatsApp Channel

WhatsApp Channel

Instagram

Instagram

Facebook

Facebook

X (Twitter)

X (Twitter)

Debanking of the account/s seems to be totally at strange in advance country like UK when in Indian PM Naendra Modi Government opened 15 Milllion bank accounts under the “PRADHAN MANTRI JAN DHAN YOJANA” in order to make people of the country participate in economic development of the country.